Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) has become the de-facto standard protocol for voice-over-IP (VoIP) phone systems. What does it do and why has it won out over other protocols? We address these questions and more in this article.

History

SIP was originally designed in 1996 and standardized in 1999 by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) in RFC 2543. The goal of its founding developers and of the standardization organization that has since adopted it has been to provide a signaling and call setup protocol for IP-based communications that can support the call processing functions and features provided by the public switched telephone network (PSTN). At the same time, SIP was designed to be extendable to support additional multimedia services such as video conferencing, media streaming, and specialized functionalities, including instant messaging, presence information, file transfer, fax over IP, and even online gaming.

Unlike other telephony protocols, SIP has roots in the internet community rather than the telephony industry. SIP has been standardized by the IETF, whereas other voice protocols such as H.323 and ISDN have been traditionally associated with the International Telecommunications Union (ITU).

Functionality

One of the most misunderstood aspects of SIP is that it is not used to carry the actual media payload, be it voice or video. Rather, as its name suggests, this protocol is involved in the control mechanisms related to the initiation and termination of sessions needed to allow voice and video applications to function. It defines the format of the control messages (and not the voice packets) transmitted between participants in a media exchange. Call setup, call teardown and Dual Tone Multi Frequency (DTMF) signals are just some of the call control messages that SIP transmits. These are among the features that have been employed in traditional telephony for decades, which SIP replicates within the VoIP domain.

Additional features commonplace on the PSTN and on conventional PBXs that SIP provides include call waiting, call hold, conferencing, call forwarding and call park, among many others. SIP was designed to mimic the functionality of the PSTN and conventional PBXs to avoid the need for retraining users when moving from conventional to IP telephony. The goal was to allow a user to use a SIP-enabled telephone without any change in the tones, functionality and general feel of the calling experience that users are familiar with.

However, SIP is not limited to just reproducing features available on conventional telephony systems – it was designed to go beyond that and incorporate advanced features and functionalities that take advantage of the IP infrastructure upon which SIP is based. This is why organizations have increasingly adopted SIP as the voice protocol of choice within their private networks. VoIP systems based on SIP can easily expand the VoIP network services by adding video, presence as well as mobile users to their existing infrastructure with very little intervention into the existing system. It offers a flexible and scalable solution, with the addition of features often being as simple as obtaining a license, a software package, or a system server.

SIP registration

SIP has a client-server architecture and primarily functions with a registration mechanism whereby SIP clients, such as an IP telephone or software running on a PC or a mobile phone, register to a SIP server, also known as an IP PBX. Once registered, a SIP client will be able to make calls based on the allowances provided by the configuration of the SIP server. Depending on how the IP PBX is configured, calls can be made either using a string of digits, just like traditional telephony, or by the SIP Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) which is used as the username of the SIP client. The SIP URI has the form of sip:username@host where host is the IP address or DNS name of the client.

Where is the voice?

If SIP doesn’t actually carry the voice packets, how is voice transferred between VoIP endpoints? SIP works in tandem with other protocols that transmit the voice information as payload. These include Real-time Transport Protocol (RTP) and RTP Control Protocol (RTCP), which are both UDP-based protocols. This means that SIP message exchange and voice packet exchange occur over two separate sessions, or channels. They are essentially two independent communication streams between endpoints that are distinguished by the Transport Layer port numbers used: one for signaling, one for voice. This is a similar arrangement to traditional ISDN circuits that separate the signaling from the voice channels, where there is one D (data) channel and 23 B (bearer) channels per 24-channel ISDN PRI circuit.

End-to-end connectivity

Another interesting and somewhat counter-intuitive aspect of SIP, and of VoIP in general, is the fact that the actual voice traffic travels from endpoint to endpoint without having to physically pass through the IP PBX. Voice packets travel over the IP infrastructure from IP endpoint to IP endpoint directly. Only some SIP signaling is necessarily transferred via the IP PBX to provide the advanced features mentioned under “Functionality” above. This is the case for communication between two IP phones that are on the same IP PBX system. In cases where the IP phone is communicating with the PSTN via a media gateway, the communication of voice packets occurs between the IP Phone and the local gateway. (Click here to download TeleDynamics’ Ultimate Guide to Media Gateways.)

Example of SIP operation

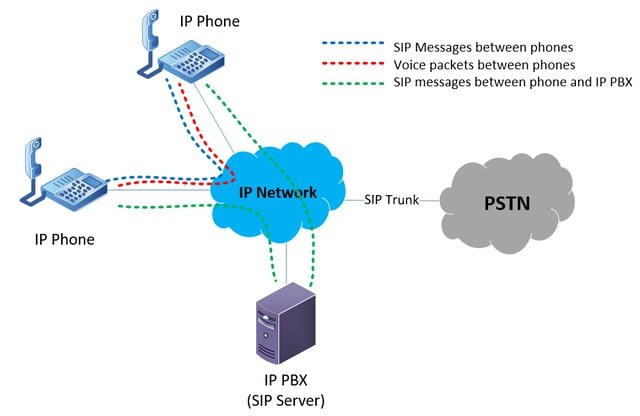

The following diagram shows an internal IP network of an organization with two IP phones, an IP PBX and a connection to the PSTN via a SIP trunk. The diagram depicts the different types of communication streams that take place for the call.

During a conversation between the two IP phones, SIP messages are exchanged between the phones and the IP PBX that deal with call setup, call teardown, DTMF tones and other controls. SIP messages are also exchanged between the two phones directly. These messages include functionalities such as codec choice and off-hook and on-hook messages. And finally, the actual voice packets travel between the two phones directly, without the aid of an intermediary device.

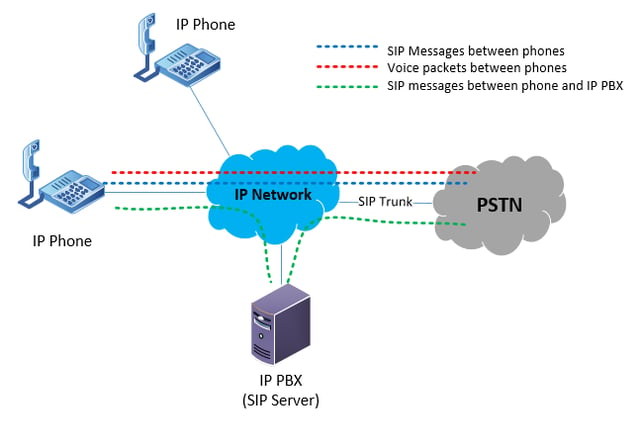

In cases where the call is initiated from inside the organization to an outside destination, once again, the same set of SIP and voice packet communications takes place, but this time, they occur with the SIP entity that exists on the PSTN. This may be a gateway within the telco’s network or it may be a SIP endpoint. This arrangement is depicted in the diagram below.

CONCLUSION

SIP is an exceptionally well designed, flexible and scalable protocol for IP voice and media. It provides a user experience almost identical to the PSTN while offering a myriad of productivity-enhancing features and services that, in today’s fast-evolving world, are indispensable. Because of this, there is no discernable end to the use of SIP as the de-facto VoIP standard, nor has there emerged any other protocol that has threatened its rule. While traditional telephony protocols and services are steadily on the decline, SIP’s future seems to be secured for at least a generation, which is all the more impressive when you consider the tremendous speed at which changes occur in the ICT industry.

You may also like:

SIP outlook for 2018: market growth strong to 2020

WAN connections and the SIP trunk: What's the connection?

Comments